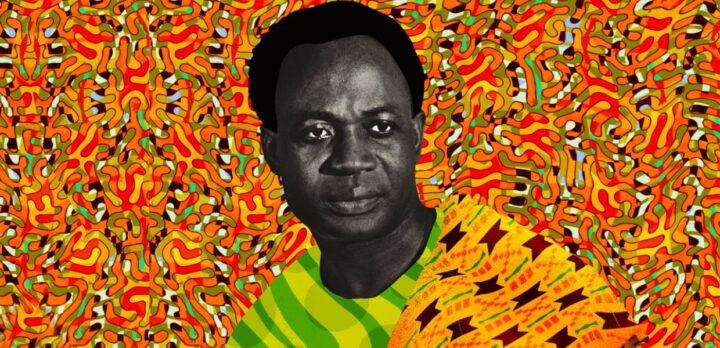

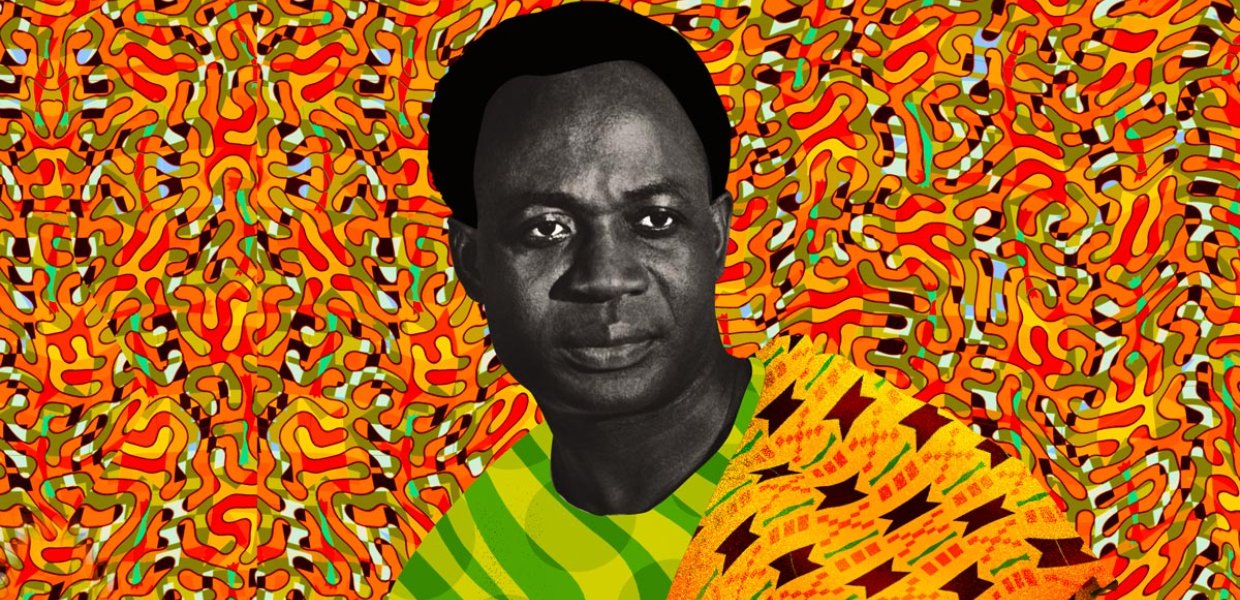

In the heart of West Africa lies a man whose name reverberates with defiance, strategy, and audacity: Ibrahim Traoré, the 35-year-old (maybe 36 by the time of this writing) leader who rose from obscurity to seize the reins of Burkina Faso. Like a force of nature, Traoré emerged amid the chaos of political instability, carving his path not with careful diplomacy but with decisive, unapologetic action. His story is a testament to the power of timing, strategy, and sheer will.

The Rise of a Revolutionary

Traoré’s rise to power reads like a modern playbook on seizing opportunity. Born in Bondokuy, a small town far removed from the urban political chessboards of Ouagadougou, Traoré was initially a soldier—a man of discipline and resilience. He studied at the University of Ouagadougou, sharpening his intellectual arsenal before fully committing to his military career. It wasn’t long before his peers noticed his ability to inspire loyalty and galvanize action.

Amid the rising tide of jihadist insurgencies and the waning influence of Western-backed leadership in Burkina Faso, Traoré saw his moment. With the kind of audacity that makes history remember names, he staged a coup in September 2022, ousting interim leader Paul-Henri Damiba. Traoré’s move wasn’t just about power—it was about reclaiming sovereignty for Burkina Faso.

Who Is Ibrahim Traoré?

The Art of Command: As Robert Greene would put it, Traoré plays to the laws of power with precision. His leadership style is a masterclass in Law 15: Crush Your Enemy Totally—his rhetoric and actions leave no room for doubt about his intentions. Traoré has openly rejected the influence of former colonial powers, turning instead toward alliances that align with his vision of independence. His unapologetic stance against France, once the dominant influence in Burkina Faso, has garnered both admiration and criticism.

Curtis “50-Cent” Jackson might liken Traoré’s strategy to the hustler’s mindset—understanding that power comes not just from control but from perception. Traoré has positioned himself as the voice of a new generation of African leaders unafraid to challenge the status quo. His decisions are bold and, at times, controversial, but they are undeniably effective in consolidating his power.

As for Traoré himself, his vision for the future and his policy directions have impacted Burkina Faso in various ways that I’ll discuss next. Whether his ideologies align with radicalism or simply represent a break from the status quo is worth scrutinizing and that’s exactly what we’ll explore in the following segment.

Ibrahim Traoré: Assessing the Label ‘Black Radical’

The term ‘Black Radical’ can evoke a spectrum of meanings, from empowering progress to unwarranted militancy. I took a closer look at Ibrahim Traoré’s political principles, actions, and the policies he champions. His trajectory so far doesn’t fit the narrow confines of what some might hastily label as radical. Instead, his focus appears to be on addressing the immediate needs and aspirations of the people of Burkina Faso.

The People’s Champion?

Traoré’s charisma lies in his ability to embody the aspirations of the Burkinabé people. His youth, military background, and direct approach have struck a chord in a nation weary of political corruption and foreign exploitation. By rejecting traditional power structures and embracing a populist narrative, Traoré has harnessed Law 27: Play on People’s Need to Believe. His promises to restore security and dignity resonate deeply with a population yearning for change.

But every revolutionary faces challenges. Traoré’s leadership is under constant scrutiny, both domestically and internationally. Critics argue that his alliances with non-traditional powers, like Russia through the Wagner Group, could destabilize the region further. Others worry that his strongman tactics might erode democratic processes. Yet Traoré seems undeterred, playing the long game in a region where short-term survival often dictates leadership.

Is Ibrahim Traoré A Black Radical?

The commentary on BlackRadicals.com surrounding Ibrahim Traoré highlights the nuances that come with leadership and social change. Through a responsible approach to journalistic storytelling, it aims to shed light on figures like Traoré and the complex socio-political landscapes they navigate.

In balancing revolutionary zeal with the practicalities of governance, Traoré’s administration will ultimately be judged by its ability to enact change and uplift its people. It’s a balancing act, respecting the heritage of black leadership while pursuing a pragmatic and inclusive approach to governance.

Lessons from Traoré

Ibrahim Traoré’s story is far from over, but it already offers valuable lessons in power, resilience, and strategy. Whether he’s viewed as a savior or a disruptor depends on perspective, but one thing is certain: he commands attention.

For Traoré, the road ahead is as treacherous as it is promising. Like the great tacticians of history, his success will depend on his ability to adapt, anticipate threats, and keep his people’s faith. But if his meteoric rise has taught us anything, it’s that Ibrahim Traoré is a man who thrives in the unpredictable—and in the end, that might just be his greatest weapon.

This post is sponsored by our good friends at WA; turn your hobbies, passions, and extracurricular activities in a content incubator for others to become inspired. Visit WA-Site Rubix today and get a free account for your journey!

Thank you for being here; stay black, get radical!

#blackradicals